As the sophistication of virtual reality (VR) increases, so does an old-school problem: motion sickness.

Megan Charity, a senior in the Virginia Commonwealth University College of Engineering’s computer science program, aims to give users an immersive — and nausea-free — ride through virtual environments.

“I’m studying low-acceleration vehicles and motion sickness in virtual reality,” Charity said. “In layman’s terms, I’m building a skateboard in VR and seeing if people get sick when they ride it.”

Motion sickness happens when what the eye sees doesn’t match what the part of the inner ear that deals with balance perceives. That disconnect is high in VR, where users are navigating large visual spaces but staying physically in place.

People currently travel through virtual worlds in several ways, none of them satisfactory, Charity explained.

Teleportation lets the user point, click and jump instantly to a new spot. It is low on the nausea-scale but also unnatural and jerky. Motion controllers, which require users to walk in place or swing their arms to move through the space, are tiring when used extensively. Joysticks let users point and zoom through a virtual space at a fixed speed — more natural than other methods, but hard to master and more likely to cause cybersickness.

Charity, an avid gamer, was well versed in all those methods. She wondered if virtual vehicles, which have not been explored fully in research, could reduce cybersickness and more fully engage the user in the virtual environment.

She began investigating last summer as a National Science Foundation Research Education for Undergraduates (REU) participant at the University of Minnesota. Charity hypothesized that a low-acceleration vehicle, which would experience little drag while moving, might fit the bill. She knew exactly which one she wanted to design.

“I’m a big skateboarder but I didn’t have my skateboard while I was researching in Minnesota,” she said. “That made me want to bring a virtual skateboard system into being.”

The skateboard she made lets users glide smoothly through virtual worlds at their own pace and enjoy the view. It gives users control and the ability to interact much more with the depth of their surroundings. Most important, these features make the skateboard more user-directed and less likely to cause cybersickness.

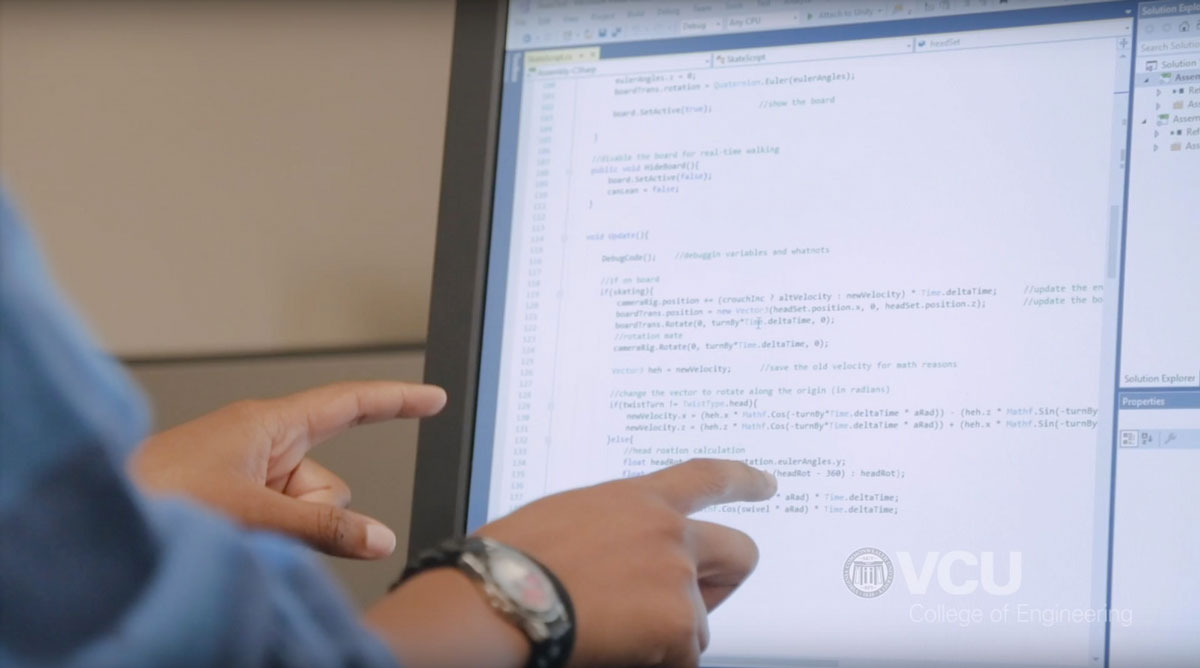

Behind the fun, easy skateboard ride are thousands of equations and lines of code.

“I was doing geometry and calculus for a week just trying to code the hand alone,” she recalled. “I kept getting sick when I didn’t get the code right.”

Once she solved those problems, she was only a fraction of the way there. “At first, you feel like you’re writing the program for yourself. The beta testers show you you’re really writing for other people,” she said. Writing — and rewriting — code is an enjoyable part of the process for Charity.

“I love code because it’s a language,” she said. “At one time, I wanted to be a writer. When I discovered computer science, I saw that coding is really just writing — with math added in.”

Charity is continuing to develop the VR skateboard with guidance from her mentor, Bridget McInnes, Ph.D., assistant professor of computer science. McInnes thinks Charity’s innovation is an advance toward interfaces that can keep up with VR’s rapid evolution. “We’re seeing more and more VR in the military, in pilot training, in shipbuilding,” she said. “Being allowed to traverse these complex virtual worlds without throwing up is a major step.”

The skateboard look and feel appeals to specific demographics, but McInnes pointed out that Charity’s technology could be adapted to other virtual vehicles including scooters.

Charity, who is a VCU College of Engineering Wright Scholar, will go to graduate school next year. She credits McInnes with inspiring and challenging her.

Charity recently demonstrated the skateboard to visitors from the VCU Center for Clinical and Translational Research, the Veterans Administration and the BuildRVA makerspace. She said it was because of McInnes that she was able to participate in an REU and create a VR skateboard at all. “You did this because of you,” McInnes countered.

“This is a project that Megan set up herself and completed herself. To do something like this as an undergrad is phenomenal — it would be fantastic for a grad student,” McInnes said. “Megan owns it.”